Glaucoma – Services and implications from Glaucoma Specialist in Kolkata

What is glaucoma?

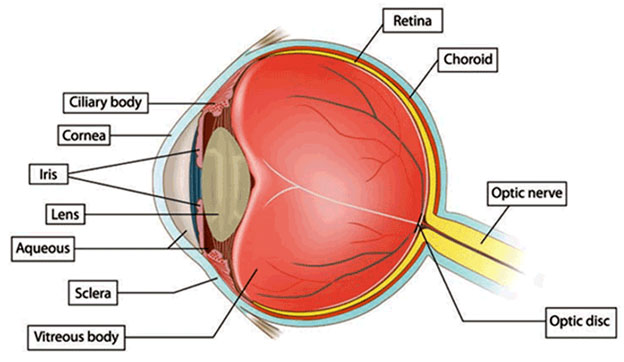

A tough white covering called the sclera protects the eye. Part of the white sclera can be seen in the front of the eye. A clear, delicate membrane called the conjunctiva covers the sclera.

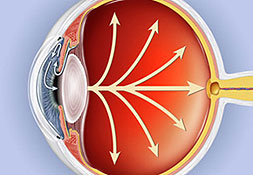

At the front of the eye is the cornea. The cornea is the clear part of the eye’s protective covering. It allows light to enter the eye. The iris is the colored part of the eye that contracts and expands so the pupil can let just the right amount of light into the eye. The light is directed by the pupil to the lens. The lens focuses the light onto the retina (lining the back of the eye). Nerve fibers in the retina carry images to the brain through the optic nerve.

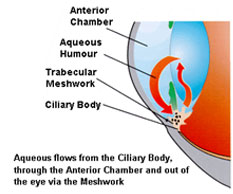

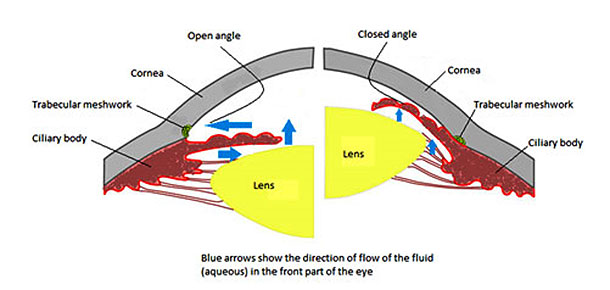

- The front part of the eye is filled with a clear fluid called intraocular fluid or aqueous humor, made by the ciliary body. The fluid flows out through the pupil. It is then absorbed into the bloodstream through the eye’s drainage system.

- This drainage system is a meshwork of drainage canals around the outer edge of the iris. Proper drainage helps keep eye pressure at a normal level. The production, flow, and drainage of this fluid is an active continuous process that is needed for the health of the eye.

- The inner pressure of the eye (intraocular pressure or IOP) depends upon the amount of fluid in the eye. If your eye’s drainage system is working properly then fluid can drain out and prevent a buildup. Likewise, if your eye’s fluid system is working properly, then the right amount of fluid will be produced for a healthy eye. Your IOP can vary at different times of the day, but it normally stays within a range that the eye can handle.

In most types of glaucoma, the eye’s drainage system becomes clogged so the intraocular fluid cannot drain. As the fluid builds up, it causes pressure to build within the eye. High pressure damages the sensitive optic nerve and results in vision loss.

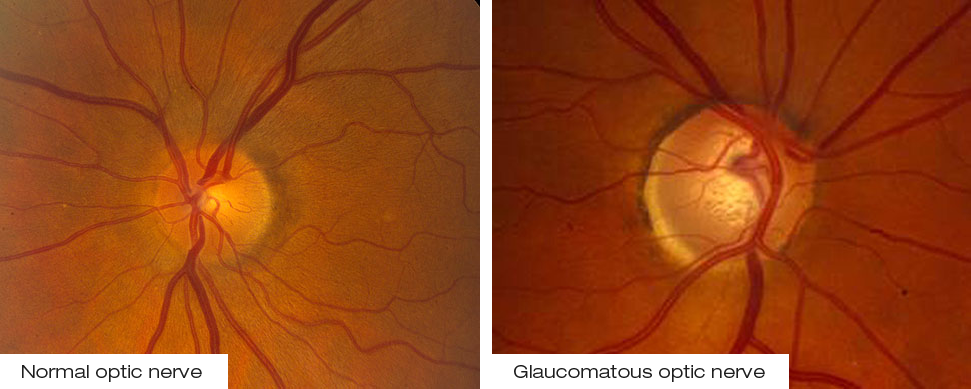

You have millions of nerve fibers that run from your retina to the optic nerve. These fibers meet at the optic disc. As fluid pressure within your eye increases, it damages these sensitive nerve fibers and they begin to die. As they die, the disc begins to hollow and develops a cupped or curved shape. If the pressure remains too high for too long, the extra pressure can damage the optic nerve and result in vision loss.

It was once thought that high intraocular pressure (IOP) was the main cause of this optic nerve damage. Although IOP is clearly a risk factor, we now know that other factors must be involved because people with “normal” IOP can experience vision loss from glaucoma.

Aqueous humor is the clear, watery fluid that is continually produced inside the eye. It is different from your tears. Tears are produced by glands outside of the eye and moisten the outer surface of the eyeball.

Glaucoma often affects both eyes, usually to varying degrees. One eye may develop glaucoma quicker than the other.

The eye ball contains a fluid called aqueous humour which is constantly produced by the eye, with any excess drained though tubes.

Glaucoma develops when the fluid cannot drain properly and pressure builds up, known as the intraocular pressure.

This can damage the optic nerve (which connects the eye to the brain) and the nerve fibres from the retina (the light-sensitive nerve tissue that lines the back of the eye).

Types of glaucoma

There are several types of glaucoma. The two main types are open-angle and angle-closure. These are marked by an increase of intraocular pressure (IOP), or pressure inside the eye.

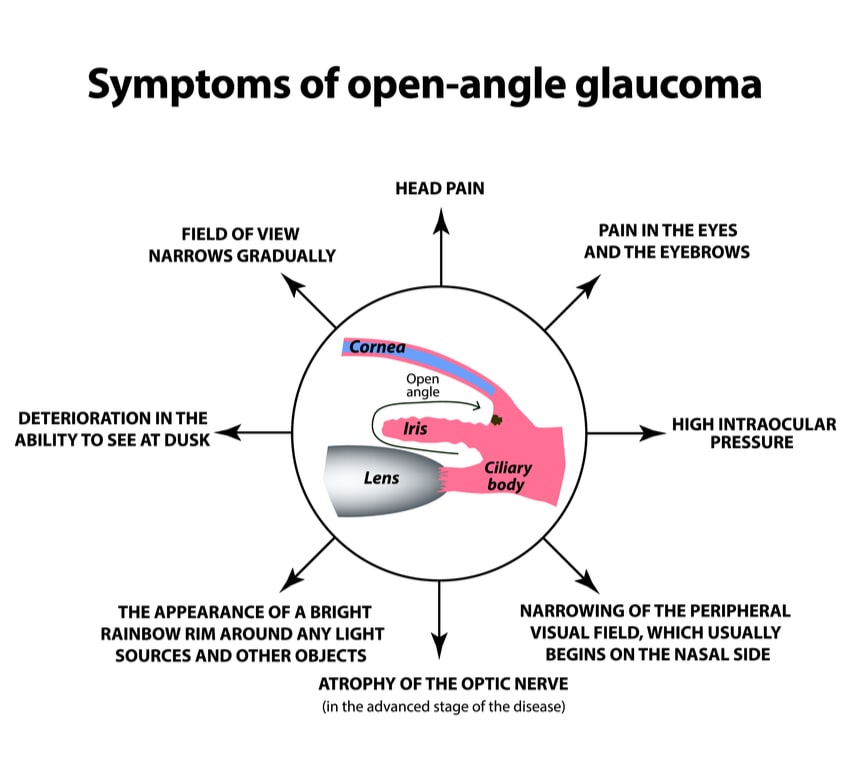

Open Angle Glaucoma

Open-angle glaucoma, the most common form of glaucoma, accounting for at least 90% of all glaucoma cases:

a) Is caused by the slow clogging of the drainage canals, resulting in increased eye pressure

b) Has a wide and open angle between the iris and cornea

c) Develops slowly and is a lifelong condition

d) Has symptoms and damage that are not noticed.

“Open-angle” means that the angle where the iris meets the cornea is as wide and open as it should be.

Open-angle glaucoma is also called primary or chronic glaucoma.

Angle Closure Glaucoma

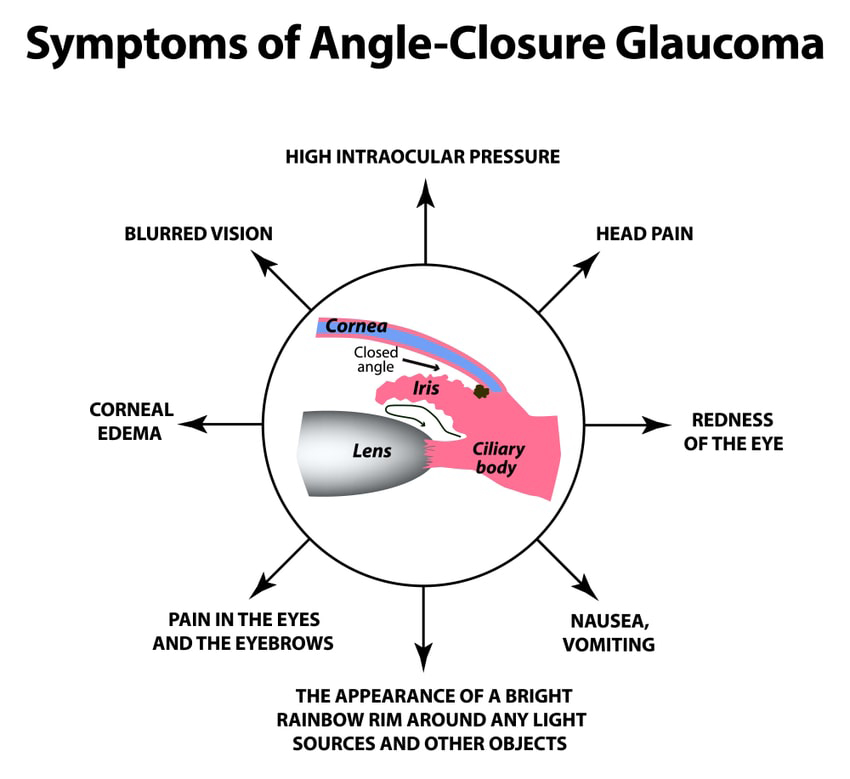

Angle-closure glaucoma, a less common form of glaucoma:

a) Is caused by blocked drainage canals, resulting in a sudden rise in intraocular pressure

b) Has a closed or narrow angle between the iris and cornea

c) Develops very quickly. Has symptoms and damage that are usually very noticeable

d) Demands immediate medical attention.

It is also called acute glaucoma or narrow-angle glaucoma. Unlike open-angle glaucoma, angle-closure glaucoma is a result of the angle between the iris and cornea closing.

Also called low-tension or normal-pressure glaucoma. In normal-tension glaucoma the optic nerve is damaged even though the eye pressure is not very high. We still don't know why some people’s optic nerves are damaged even though they have almost normal pressure levels.

This type of glaucoma occurs in babies when there is incorrect or incomplete development of the eye's drainage canals during the prenatal period. This is a rare condition that may be inherited. When uncomplicated, microsurgery can often correct the structural defects. Other cases are treated with medication and surgery.

With inflammatory glaucoma the inflammation can either raise or lower the IOP (intraocular pressure). Inflammation causes white cells to form in the liquid in the front of the eye. The cells get trapped in the trabecular meshwork (the “drain”), blocking it. The fluid also becomes thicker and less likely to pass through the drain, and the trabecular beams that make up the drain swell, making the pores between them smaller. Inflammation can also release prostaglandins that increase the flow of fluid out of the eye between the muscle bundles of the eye.

Traumatic glaucoma can occur when trauma injures the trabecular meshwork, the “drain” in the eye. Scarring ensues, and the drain works less well. Early on, blood and inflammatory material can also block the trabecular meshwork. Often there are signs of injury to the drain in the eye. One sign is called an angle recession. With this sign, the iris root is pulled posteriorly away from the trabecular meshwork. That is easily seen during gonioscopy. There is at least a 5% chance that someone with serious eye trauma and an angle recession will develop glaucoma later in life, even if the glaucoma is not present for several years after the trauma.

Pigmentary glaucoma is a secondary glaucoma caused by an accumulation of pigment in the trabecular meshwork of the eye, blocking the outflow of fluid. Pigmentary glaucoma is usually found in near-sighted individuals in their late 20’s to early 40’s and is more common in males than in females.

Iridocorneal Endothelial syndrome or ICE syndrome is a grouping of three closely linked conditions: iris nevus (or Cogan-Reese) syndrome; Chandler’s syndrome; and essential (progressive) iris atrophy, which together also spell the acronym ICE. ICE syndrome is caused by the diseased lining of the cornea, which grows over the drain in the eye, blocking it, and over the iris, causing stretching and a lack of blood supply.

- Secondary Glaucoma

Pigmentary Glaucoma

Pseudoexfoliative Glaucoma

Traumatic Glaucoma

Neovascular Glaucoma

- Irido Corneal Endothelial Syndrome (ICE)

How do I know whether I have glaucoma?

Symptoms of Glaucoma:

95% patients with glaucoma do not have any symptoms. Glaucoma is a silent disease that cannot be detected or felt by the patient since central vision remains unaffected till the late stages of the disease. Hence it is rightly called as the ‘sneak thief of sight’. It is usually detected during a routine eye checkup. Symptoms patients experience in various types of glaucoma.

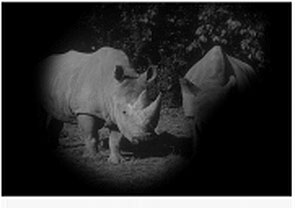

In cases of chronic glaucoma, there are usually no noticeable symptoms because the condition develops very slowly. People don't often realise their sight is being damaged because the first part of the eye to be affected is the outer field of vision (peripheral vision). Vision is lost from the outer rim of the eye, slowly working inwards towards the centre.

Acute angle-closure glaucoma develops rapidly. Symptoms are often severe. They include:

- Intense pain

- Redness of the eye

- Headache

- Tender eye area

- Seeing halos or 'rainbow-like' rings around lights

- Misty vision

- Loss of vision in one or both eyes that progresses very quickly

Secondary glaucoma is caused by other conditions, such as uveitis (inflammation of the middle layer of the eye). It can also be caused by eye injuries and certain treatments, such as medication or operations.

It's possible for the symptoms of glaucoma to be confused with the symptoms of the other condition. For example, uveitis often causes painful eyes and headaches.

However, the glaucoma may still cause misty vision and rings or halos around lights.

Recognising the symptoms of developmental glaucoma (also known as congenital glaucoma) can be difficult due to the young age of the baby or child. However, your child may display symptoms, such as:

- Large eyes due to the pressure in the eyes causing them to expand

- Being sensitive to light (photophobia)

- Having a cloudy appearance to their eyes

- Having watery eyes

- Jerky movements of the eyes

- Having a squint, which is an eye condition that causes one of the eyes to turn inwards, outwards or upwards, while the other eye looks forward.

Are you at risk for glaucoma?

Everyone is at risk for glaucoma. However, certain groups are at higher risk than others.

People at high risk for glaucoma should get a complete eye exam, including eye dilation, every one or two years. The following are groups at higher risk for developing glaucoma.

Glaucoma is much more common among older people. You are six times more likely to get glaucoma if you are over 60 years old.

The most common type of glaucoma, primary open-angle glaucoma, is hereditary. If members of your immediate family have glaucoma, you are at a much higher risk than the rest of the population.

Family history increases risk of glaucoma four to nine times.

Some evidence links steroid use to glaucoma. A 1997 study reported in the Journal of American Medical Association demonstrated a 40% increase in the incidence of ocular hypertension and open-angle glaucoma in adults who require approximately 14 to 35 puffs of steroid inhaler to control asthma. This is a very high dose, only required in cases of severe asthma.

Injury to the eye may cause secondary open-angle glaucoma. This type of glaucoma can occur immediately after the injury or years later.

Blunt injuries that “bruise” the eye (called blunt trauma) or injuries that penetrate the eye can damage the eye’s drainage system, leading to traumatic glaucoma.

The most common cause is sports-related injuries such as baseball or boxing.

Other possible risk factors include:

- High myopia (nearsightedness)

- Central corneal thickness less than 0.50 mm.

Glaucoma Evaluation

Early detection, through regular and complete eye exams, is the key to protecting your vision from damage caused by glaucoma. A complete eye exam includes five common tests to detect glaucoma.

It is important to have your eyes examined regularly. Your eyes should be tested:

a) before age 40, every two to four years

b) from age 40 to age 54, every one to three years

c) from age 55 to 64, every one to two years

d) after age 65, every six to 12 months Anyone with high risk factors should be tested every year or two after age 35.

Anyone with high risk factors should be tested every year or two after age 35.

To be safe and accurate, five factors should be checked before making a glaucoma diagnosis:

| Examining… | Name of Test |

| The inner eye pressure | Tonometry |

| The shape and color of the optic nerve | Ophthalmoscopy (dilated eye exam) |

| The complete field of vision | Perimetry (visual field test) |

The angle in the eye where the iris meets the cornea | Gonioscopy |

| Thickness of the cornea | Pachymetry |

Regular glaucoma check-ups include two routine eye tests: tonometry and ophthalmoscopy.

Tonometry measures the pressure within your eye. During tonometry, eye drops are used to numb the eye. Then a doctor or technician uses a device called a tonometer to measure the inner pressure of the eye. A small amount of pressure is applied to the eye by a tiny device or by a warm puff of air.

The range for normal pressure is 12-22 mm Hg (“mm Hg” refers to millimeters of mercury, a scale used to record eye pressure). Most glaucoma cases are diagnosed with pressure exceeding 20mm Hg. However, some people can have glaucoma at pressures between 12 -22mm Hg. Eye pressure is unique to each person.

This diagnostic procedure helps the doctor examine your optic nerve for glaucoma damage. Eye drops are used to dilate the pupil so that the doctor can see through your eye to examine the shape and color of the optic nerve.

The doctor will then use a small device with a light on the end to light and magnify the optic nerve. If your intraocular pressure is not within the normal range or if the optic nerve looks unusual, your doctor may ask you to have one or two more glaucoma exams: perimetry and gonioscopy.

Perimetry is a visual field test that produces a map of your complete field of vision. This test will help a doctor determine whether your vision has been affected by glaucoma. During this test, you will be asked to look straight ahead and then indicate when a moving light passes your peripheral (or side) vision. This helps draw a "map" of your vision.

Do not be concerned if there is a delay in seeing the light as it moves in or around your blind spot. This is perfectly normal and does not necessarily mean that your field of vision is damaged. Try to relax and respond as accurately as possible during the test.

Your doctor may want you to repeat the test to see if the results are the same the next time you take it. After glaucoma has been diagnosed, visual field tests are usually done one to two times a year to check for any changes in your vision.

This diagnostic exam helps determine whether the angle where the iris meets the cornea is open and wide or narrow and closed. During the exam, eye drops are used to numb the eye. A hand-held contact lens is gently placed on the eye. This contact lens has a mirror that shows the doctor if the angle between the iris and cornea is closed and blocked (a possible sign of angle-closure or acute glaucoma) or wide and open (a possible sign of open-angle, chronic glaucoma).

Pachymetry is a simple, painless test to measure the thickness of your cornea — the clear window at the front of the eye. A probe called a pachymeter is gently placed on the front of the eye (the cornea) to measure its thickness. Pachymetry can help your diagnosis, because corneal thickness has the potential to influence eye pressure readings. With this measurement, your doctor can better understand your IOP reading and develop a treatment plan that is right for you. The procedure takes only about a minute to measure both eyes.

1. Retinal nerve fibre layer thickness(optical coherence tomography) : This machine measures the thickness of the retinal nerve fibers; glaucoma causes death of the nerve fibers . This instrument is useful for early detection of damage and change over a period of time.

2. Heidelberg retinal tomography (HRT) : this device documents the optic nerve and retinal nerve fiber layer and it can also be used to detect progression of the disease. It is a non-contact, rapid test.

3. Ultrasound biomiscropscopy (UBM): This device scans the front part of the eye involved in drainage of fluid ; it is an alternative to gonioscopy in case of hazy cornea, preventing its direct visualization.

Diagnosing glaucoma is not always easy, and careful evaluation of the optic nerve continues to be essential to diagnosis and treatment. The most important concern is protecting your sight. Doctors look at many factors before making decisions about your treatment.

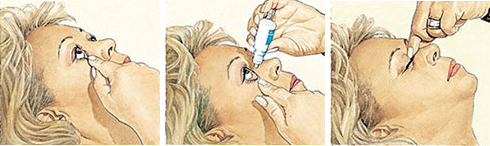

How to instill eye drop

Prescription eye drops for glaucoma help maintain the pressure in your eye at a healthy level and are an important part of the treatment routine for many people.

Always check with your doctor if you are having difficulty.

- Follow your doctor’s orders.

- Wash your hands before putting in your eye drops.

- Be careful not to let the tip of the dropper touch any part of your eye.

- If you are putting in more than one drop or more than one type of eye drop, wait fifteen minutes before putting the next drop in. This will keep the first drop from being washed out by the second before it has had time to work.

- Store eye drops and all medicines out of the reach of children.

- Start by tilting your head backward while sitting, standing, or lying down. With your index finger placed on the soft spot just below the lower lid, gently pull down to form a pocket.

- Look up. Squeeze one drop into the pocket in your lower lid. Don't blink, wipe your eye, or touch the tip of the bottle on your eye or face.

- Close your eye. Keep closed for two to three minutes without blinking. Optional: Gently press on the inside corner of your closed eyes with your index finger and thumb for two to three minutes (to keep the drops from draining into your throat and getting into your system).

- Blot around your eyes to remove any excess.

If you are still having trouble putting eye drops in, here are some tips below that may help:

Try approaching your eye from the side so you can rest your hand on your face to help steady your hand.

If shaky hands are still a problem, you might try using a 1 or 2 pound wrist weight (you can get these at any sporting goods store). The extra weight around the wrist of the hand you’re using can decrease mild shaking.

Try This. With your head turned to the side or lying on your side, close your eyes. Place a drop in the inner corner of your eyelid (the side closest to the bridge of your nose). By opening your eyes slowly, the drop should fall right into your eye.

If you are still not sure the drop actually got in your eye, put in another drop. The eyelids can hold only about one drop, so any excess will just run out of the eye. It is better to have excess run out than to not have enough medication in your eye.

Medications

A variety of options are available to treat glaucoma. These include eye drops and surgery. All are intended to decrease eye pressure and, thereby, protect the optic nerve.

Currently, eye drops are often the first choice for treating patients. For many people a medications can safely control eye pressure for years. Eye drops used in managing glaucoma decrease eye pressure by helping the eye’s fluid to drain better and/or decreasing the amount of fluid made by the eye. Drugs to treat glaucoma are classified by their active ingredient. These include: prostaglandin analogs, beta blockers, alpha agonists, and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. In addition, combination drugs are available for patients who require more than one type of medication.

- Prostaglandin analogs they work by increasing the outflow of fluid from the eye. They have few systemic side effects but are associated with changes to the eye itself, including change in iris color and growth of eyelashes (see "Side Effects" below). Depending on the individual, one of these brands may be more effective and produce fewer side effects.

- Beta blockers such as timolol are the second most often used class of medication and work by decreasing production of fluid. They are available in generic form and, therefore, are relatively inexpensive. Moreover, systemic side effects can be minimized by closing the eyes following application or using a technique called punctal occlusion that prevents the drug from entering the tear drainage duct and systemic circulation.

- Alpha agonists (Alphagan®P, iopidine®) work to both decrease production of fluid and increase drainage. Alphagan P has a purite preservative that breaks down into natural tear components and may be more effective for people who have allergic reactions to preservatives in other eye drops. Alphagan is available in a generic form.

- Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (CAIs) reduce eye pressure by decreasing the production of intraocular fluid. These are available as eye drops (Trusopt®, Azopt™) as well as pills [Diamox® (acetazolamide) and Neptazane® (methazolamide)].

- Combined medications can offer an alternative for patients who need more than one type of medication. In addition to the convenience of using one eyedrop bottle instead of two, there may also be a financial advantage, depending on your insurance plan.

Of course, no eye drop medication can be effective if it is not taken as prescribed. There are a number of reasons why people being treated for glaucoma may not take their medications.

One reason is that they simply forget! Remembering to take a daily medication is one of the challenges in the treatment of any chronic condition, and glaucoma is no exception. Some ways to help remember include tying a regular daily activity (such as brushing one’s teeth) to taking one’s medication, or setting timed reminders such as an alarm clock or cell phone.

A second factor in not taking medication as prescribed is economics. Glaucoma drugs can be expensive.

Following are potential side effects of the most commonly prescribed types of glaucoma medications.

* Prostaglandin Analogs: possible changes in eye color and eyelid skin, stinging, blurred vision, eye redness, itching, burning.

* Beta Blockers: low blood pressure, reduced pulse rate, fatigue, shortness of breath; rarely: reduced libido, depression.

* Alpha Agonists: burning or stinging, fatigue, headache, drowsiness, dry mouth and nose, relatively higher likelihood of allergic reaction.

* Carbonic Anhydrase Inhibitors: in eye drop form: stinging, burning, eye discomfort; in pill form: tingling hands and feet, stomach upset, memory problems, depression, frequent urination.

Side effects of combined medications may include any of the side effects of the drug types they contain.

YAG Peripheral Iridotmoy

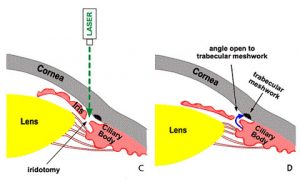

The eye is a hollow structure, and is filled with fluid, which inflates the eye and gives the eye its shape. Fluid is made inside the eye, and drains out of the eye at a relatively constant rate, so the pressure of the eye remains stable. However, in some people, especially people who are farsighted, the drain inside the eye (called “the angle”) can start to close. This is referred to as “anatomically narrow angles.”

If the angle closes, then fluid is made inside the eye, but it cannot drain out. Imagine what would happen if you kept inflating a basketball after it was already filled with air. Inside the eye, if the angle closes, then fluid will build up in the eye – causing increased eye pressure. If the pressure in the eye becomes too high, your eye will become very painful, and you may have permanent vision loss.

No. Anatomically narrow angles can cause high pressure in the eye (often referred to as glaucoma) if the angle becomes closed. Anatomically narrow angles are a risk factor for glaucoma, but it does not mean that you have glaucoma now.

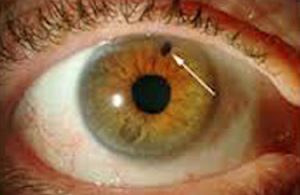

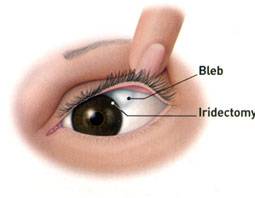

Yes. We can use a laser beam (the YAG laser) to make a microscopic hole in the iris (the colored part of the eye.) The hole (iridotomy) creates a “release valve” and creates an alternate channel for fluid to flow through the eye. The iridotomy decreases the risk of having angle closure and vision loss from glaucoma.

There is a small risk (1-2%/year) that you will develop angle closure, and severe eye pain and vision loss. Once angle closure develops, it is hard to treat. There is also the chance that the angle will close slowly and cause scarring, and slowly increase pressure in the eye. There is often no pain with chronic angle closure, and you can loose vision without being aware that your eye pressure is high.

The laser iridotomy is performed in the laser room. You do not need to go to the operating room. You do not need any blood work or a medical exam prior to the procedure. You will be awake, but your eye will be numbed. The laser procedure is brief – it takes between 1-2 minutes for the entire procedure. There are no restrictions on your activities after the procedure.

Your vision may be blurry for a few minutes after the procedure, but your vision should return shortly.

YAG laser treatment:

Some people will feel brief “twinges” of discomfort during the laser procedure. There is rarely a small amount of bleeding inside the eye, but this resolves quickly. Some people will have pain with light for a few days after the procedure. We will give you eye drops to prevent this from occurring.

There is also a risk of increased eye pressure, and we monitor your eye closely after the procedure.

No. Your vision should not get better or worse.

You will use steroid eye drops 6 times/day for 5 days. You will see Dr Sagar Bhargava after 1 week when the angle structure will be rechecked and retinal examination will be done.

Ytrium Alumnium Garnet. This is a synthetic gemstone used to create the specific wavelength of light for the laser procedure.

Surgeries

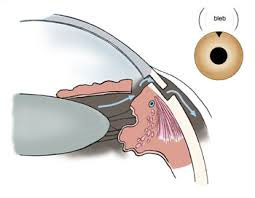

TRABECULECTOMY

Trabeculectomy is recommended to treat glaucoma when more conservative treatment such as medication or laser do not provide adequate pressure control. In glaucoma, eye pressure causes damage to the optic nerve. With damage to the nerve, there can be irreversible loss of vision, and sometimes blindness. Fortunately, there are many excellent treatments for glaucoma that can prevent or stop vision loss. Generally we start treatment with medicated eye drops.

Patients are treated with one or more drops to lower eye pressure. Unfortunately, drops don’t always lower eye pressure enough to protect a patient from further nerve damage and vision loss. Sometimes laser is an option, but laser does not work for everyone, and may not lower pressure enough. For that reason, a trabeculectomy is often the next step in treatment of glaucoma.

A trabeculectomy is a surgery designed to lower eye pressure to treat glaucoma. In a trabeculectomy, a new drain is created within the eye to allow fluid to leave the eye.This is done by removing a small piece of the natural drain in the eye and creating an opening in the sclera (the white of the eye) that is covered by a membrane on the surface of the eye (the conjunctiva). Fluid collects under the membrane (conjunctiva), forming a small elevation called a “bleb” that is under the upper eyelid.The fluid is then gradually absorbed into the body from the bleb.

- Vision – Sight may take several weeks before it returns to normal . Some patients will find their vision is ot quiet as sharp after surgery. The benefit is slowing (or stopping) the rate of deterioration of glaucoma. However the operation cannot be totally guaranteed to stop the loss of vision in your eye. Eye surgery for any condition ALWAYS carries a small risk that vision may be worse or the eye may become bind after the operation.

- Eye pressure control – Failure to lower eye pressure enough, with the need for another operation of the need to recommend pressure lowering eye drops. If the eye pressure becomes too low after the surgery further surgery may be necessary.

- Bleeding – There is a small chance of bleeding inside the eye immediately after the surgery (called suprachoroidal haemorrhage) .This may require further treatment and may ultimately result in loss of sight.

Infection- There is a small chance of infection inside the eye after surgery. This may require further treatment and may ultimately result in loss of sight. The operation will make your eye more prone to infection, even in years to come. If your eye becomes painful or red or the vision becomes blurred, you should seek immediate medical help.

- Cataract – There is a reasonable chance that a cataract may develop some years after the surgery. This may require an operation.

- Irritation – Irritation (grittiness) or discomfort in the eye that may persis.

- Droopy Eyelid – Eyelid may become droopy on side of operation.

SHUNT SURGERIES

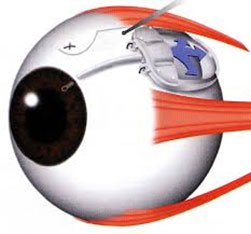

One of the newer types of surgery, a tube shunt, is a flexible glaucoma drainage device that is implanted in the eye to divert aqueous humor (the fluid inside the eye) from the inside of the eye to an external reservoir. The shunt is shaped like a miniature computer mouse with a tube at the end of it. The tube portion enters the front of the eye, or anterior chamber, while the “mouse” or “plate” portion of the implant sits on the surface of the eyeball and is covered by the eyelid. The fluid that collects is then absorbed by the eye’s own veins and transported out of the eye cavity.

The tube shunt is made of silicone or polypropylene, a material that won’t break down in the body. The entire implant is covered with the eye’s own external covering. The procedure is done as outpatient surgery.

Traditionally, tube shunts were used to control eye pressure in patients in whom traditional eye surgery to relieve fluid pressure (trabeculectomy) had previously failed, or in patients who have had previous surgeries or trauma that caused substantial scarring of the conjunctiva. Tube shunts have also been successful in controlling eye pressure in other types of glaucoma, such as glaucoma associated with uveitis or inflammation, neo vascular glaucoma (associated with diabetes or other vascular eye diseases), pediatric glaucoma, traumatic glaucoma, and others.

The vast majority of tube shunt procedures are successful and prevent the progression to blindness that can occur with glaucoma. Nonetheless, it is important for you to understand the risks and benefits before electing a tube shunt surgery. Any of the complications described below can occur even with the best surgical techniques.

Uncommon or rare complications include bleeding inside the eye; infection; fluid buildup behind the retina (choroidal detachment, which is not the same as retinal detachment); double vision with some types of implants; and tube-related complications. Bleeding inside the eye can be a very serious complication; for this reason, some surgeons will ask you to stop all blood thinner medications for at least one week before the surgery. Make sure you ask your general doctor if this is acceptable. If not, a discussion should occur between the ophthalmologist and the general doctor before the surgery.

Infection is another risk. As a precaution, ophthalmologists give antibiotics before, during, and after the surgery in addition to practicing sterile. However, on very rare occasions, infection inside the eye occurs anyway. This can be a very serious problem and may threaten vision. With tube shunt surgery, infection can occur months to years after the actual operation, sometimes requiring shunt removal. Your eye doctor

resume glaucoma medications down the road, or even right after surgery. In addition, sometimes a repeat surgery is required. Also, despite successful surgery, your vision may become worse from continuing degenerative changes in the eye. Cataracts may be accelerated by any of these operations. Fortunately, cataracts are relatively easy to fix surgically.

Tube-related complications can also occur, and some of these relate to placement of the tube inside the eye. If the tube is placed too close to the cornea, it can cause the cornea to swell. This is particularly a problem if you already have a corneal transplant. In some higher risk cases, the surgeon will elect to place the tube in the back of the eye; which means a retina surgeon may perform the procedure alongside your glaucoma surgeon. Another risk entails placing the tube too close to the iris, which can cause it to become clogged with iris tissue. Still another risk is of blood clots developing after the surgery.

Most of the above types of tube complications will resolve with time or with the help of an in-office laser procedure. There is one more type of complication to mention: over time, with or without infection, the tube can protrude through the delicate surface tissues of the eye, or conjunctiva, to where it’s exposed and visible on the eyeball. If that happens, it will require another trip to the operating room so the tube can be re-implanted.

Unfortunately, the damage that is caused by glaucoma is permanent and not yet reversible. Consequently, it is extremely rare for a tube shunt procedure to bring about any improvement in vision. Instead, the main benefit and reason for having the procedure is preventive; i.e., without it, vision may grow worse or, in rare cases, be totally lost. In most cases, doctors will not recommend a tube shunt unless they believe you to be at risk for vision loss. Therefore, for most patients, the benefits of the surgery tend to outweigh the risks, but this has to be evaluated separately for each patient.